In Rhode Island, a Model for Upending Health Inequity

- Published By

- Community Commons

This article was written by Julie Ryan. It was originally posted on March 2, 2017 in the Building Healthy Places Network blog.

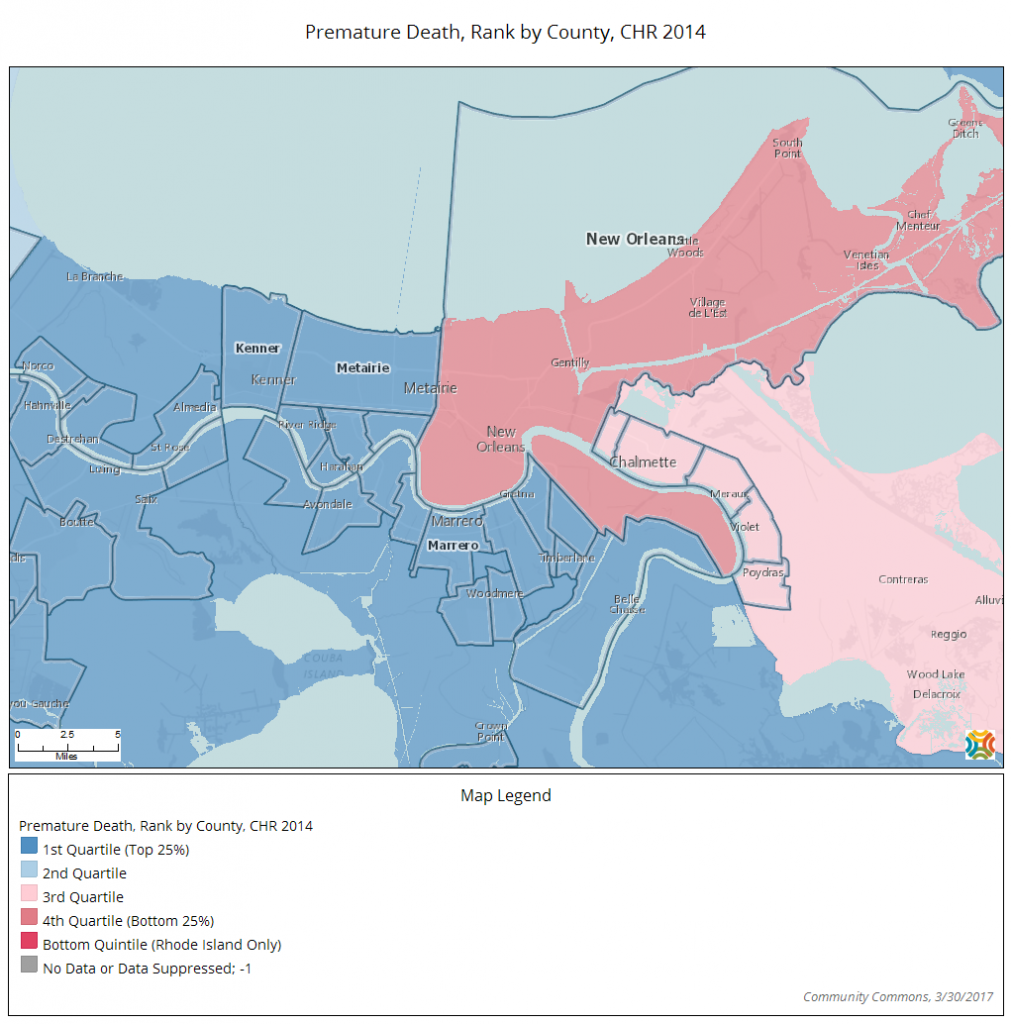

Looking at a map of the places they call home, most people can easily point to notably affluent areas versus the ones that have dilapidated homes, under-resourced schools and unsafe sidewalks—places more likely to be cut through by a six-lane highway, or to host a polluting factory rather than a supermarket stacked with fresh food or a tree-shaded playground.

In the last decade, as public health experts have mapped these areas of social disparity, they have also begun plotting a new set of data points on health outcomes. Indeed, it probably doesn’t surprise anyone that healthier living environments give rise to healthier lives. And longer lives, too. For example, a baby born in the Lakeview area of New Orleans can expect to live to 80, whereas one born just a few miles away in Treme has a life expectancy of 55.

Twenty five years. It’s hard to imagine a starker reflection of unequal opportunity. But this doesn’t have to be.

When government, community leaders and public health advocates collaborate, these disparities don’t have to be inevitable. In fact, this is how my organization, the Local Initiatives Support Corp. (LISC), approaches our work to help improve health in low-income places all across the country. We know we can begin to upend health inequities by focusing our combined efforts to support well-being in the neighborhoods that need it most.

That’s the idea behind a path-breaking initiative launched last year by the Rhode Island Department of Health to establish ten “health equity zones” (HEZ) across this small New England state.

Health-focused Cross-Sector Collaboration

Each health zone is a contiguous area—as small as a few city blocks or as large as a county—with higher-than-average health risks and burdens. And each is managed by a local “backbone” agency.

The variety of these lead agencies is part of the initiative’s novelty and strength. They include an extensive community health center with multiple sites and an organization that supports domestic-violence survivors as well as a municipality, an affordable housing developer, and a school district. LISC serves as backbone agency for Pawtucket and Central Falls, two small cities north of Providence.

To get the health zones we are leading up and running, these we have partnered with everyone from police departments to community health centers. We’ve also reached out to residents to gauge needs and priorities, and have developed and begun to implement multi-strategy action plans for community health.

Some strategies are targeting the physical environment, like promoting bike lanes and improving vacant properties. Others are focusing on behavioral change, disease prevention, and education. Still others are promoting access to nutritious food, health services, and even job training. In just the first year of implementation, we have filled six diabetes prevention classes and helped launch 76 community gardens on public housing land, as well as a community health fellowship program for residents.

Even before becoming the lead agency for a health zone, LISC was working to revitalize Pawtucket and Central Falls. We invested in safe and affordable housing there and worked with the police and other partners to get help for local sex workers at risk for addiction, violence, homelessness, and sexually transmitted disease. In many ways, the complex, cross-disciplinary crime reduction work we support dovetails perfectly with this approach to improving health.

As part of the health zone, we’re continuing to use our comprehensive lens to better the lives of local residents by investing in groups working to develop community gardens and urban farms, for instance, and helping homeowners make necessary repairs, avoid foreclosure, and get rid of lead.

But what’s new isn’t the interventions themselves—established approaches with proven effectiveness—it’s the way they’re bundled for maximum impact in particular places, and the way they push the very concept of health promotion beyond the confines of the doctor’s office and disease-specific efforts.

Guided by Community Input

In the Central Falls/Pawtucket HEZ, nearly a third of residents live in poverty and one out of three are recent immigrants. The area suffers high rates of teen pregnancy, early-childhood obesity, and infant mortality. Carrie Zaslow, my colleague in LISC’s Rhode Island office, says that during the agency’s “listening tour” of the area, investigators didn’t inquire a lot about resident’s physical health. The conversation was far more open-ended. What came up included concerns about income and jobs, access to healthy foods, and the need for better transportation.

One concern was voiced again and again: older people reported they had a hard time getting out, especially in winter, and faced a dearth of activities to help them stay connected—a double whammy of physical immobility and social isolation that could have a substantial impact on their health. The health zone partners created a community-service program in which teens help their elderly neighbors on snowy days by shoveling out their walks and drives. That’s just one of many practical solutions the collaborative came up with.

As Carrie Zaslow explained it to me, “A lot of how LISC has evaluated our work is through metrics like increases in income, decreases in unemployment, housing units built—how we’ve impacted the economic wellbeing of a neighborhood.” In this case, she added “we’re asking about health outcomes. Are more people who potentially have pre-diabetes in programs? Are we seeing people eating more vegetables, are they reporting that they’re exercising more? Are they able to access culturally sensitive behavioral health services?”

increases in income, decreases in unemployment, housing units built—how we’ve impacted the economic wellbeing of a neighborhood.” In this case, she added “we’re asking about health outcomes. Are more people who potentially have pre-diabetes in programs? Are we seeing people eating more vegetables, are they reporting that they’re exercising more? Are they able to access culturally sensitive behavioral health services?”

That the Rhode Island Department of Health has been able to channel millions of dollars to develop the HEZs is itself an object lesson in creative budget management. After all, it’s not as if there’s a big pot of money out there earmarked for attacking health disparities in a holistic, place-based way. Novais knows the challenge of getting taxpayer support for such work. She and her colleagues responded by pulling together federal monies targeting such areas as child and maternal health, chronic disease prevention, smoking cessation, and emergency preparedness—and focusing those resources on the work of the healthy equity zones.

A Long View of Change

Everyone involved in the health zones understood from the outset that a few years is not enough time to effect—let alone to persuasively document—changes in longevity. Instead there are two basic levels of evaluation. The most important is a fine-grained check on how well each HEZ has met the goals laid out in its own detailed action plan. So, for example, a health zone focusing on chronic disease might show how many people completed a diabetes prevention program, or the number of residents with diabetes who improved their blood-sugar control.

The second level of evaluation looks at the components of the HEZ and how well they’re run: Does the backbone agency have governance standards that are clearly spelled out? How diverse and active is the health zone’s collaborative? In addition, the health department will be studying statewide data to try to identify core indicators of success. A light switched on for me several years ago when I learned that medical care contributes only about ten percent to health and longevity—far less than the impact the environmental and social factors we experience in our homes and neighborhoods. So for all the money the United States spends on health care–and we spend more per capital than any other country—we have considerably higher rates of obesity, diabetes, and low birthweight, to name a few.

As a society, we can do better. Let’s imagine a different map, a different drive through our communities. On this one you won’t find a longevity gap; you won’t find food deserts or high rates of pediatric asthma. Everywhere you point should be a place where any one of us can live a healthy, productive life.

View Story